[This article was submitted in response to A Strategy for Human Factors/Ergonomics as a Discipline and Profession (Reprint).]

While any remarks about a subject as complex as a strategy for Human Factors and Ergonomics (HFE) have to be qualified by acknowledging the uncertainties involved, regrettably the strategy paper by Jan Dul and others in the April 2012 issue of Ergonomics is unlikely to go near to where its authors aspire.

The reason for this assessment is simple: their aspirations for the HFE community as ‘a main actor’ in speaking ‘the language of stakeholders’ with powerful people are not based on relevant evidence and they fail to even mention the core challenge facing all forms of business and organisational consulting now, namely building trust with stakeholders.

Partnering preferable to acting powerful

The authors of the strategy anchor their argument in a paper by Mitchell, R.E., Agle, B.R., Wood D.J. that offers a quite interesting conceptual analysis about stakeholders (Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review. 32(4) pp.853-896. 1997); they conclude themselves with the analysis that key stakeholders that the HFE community should dwell on are those with ‘power’, with whom they should engage in their language ‘as the main actor’. They ignore the simple fact that the analysis supporting their choice is based on zero data about the demand size of the consultancy market and about the scale and intensity of competition for attention of the target shareholders.

Following on the same path of plain disregard for elementary commercial realities, the papers’ authors present no data whatsoever about the supply side of the HFE market. This turns a blind eye to the hybrid nature of the careers of many HFE practitioners, and fails to even consider implications of how fragmented their identification with the HFE profession may be. Demographic arithmetic may not excite many in the HFE community but without reliable data about the numbers of HFE practitioners and their professional allegiances, what is presented as a strategy is actually directionless, offering no basis for decision-making or commitment.

While it is hardly difficult for the HFE community to assent with the aspiration that it should speak ‘the language of stakeholders….. as the main actor’, the strategy paper presents this aspiration without any reference to relevant trends in the marketplace for consulting in recent decades. Specifically, they show not the slightest awareness of the research on development in leadership in organisations that indicates the growing attention to the need for various forms of social intelligence; they equally turn collective blind eyes to the teachings of the pacemakers in development of consultants – statistician David Maister, lawyer Robert Galsford and former European director of management consultants Deloittes, philosophy graduate Charles Green – that trust has become the well-established the differentiating factor in the consultancy market where they characterise trust in terms of reliability, credibility, intimacy and consultants’ self-effacement. Even more pertinent, they disregard the contention of Green and his colleague Andrea Howe (‘The Trusted Advisor’s Fieldbook’ John Wiley, 2012) that evidence indicates how while professionals tend to compete in the relatively straightforward areas of ‘reliability’ and ‘credibility’, clients show allegiance towards those who display stronger evidence of qualities of self-effacement and the intimacy that warrants appropriate self-disclosure.

Like too many modern professions, the HFE one is much readier to talk and write at length about complex cognitive challenges than the much less straightforward ones that touch on emotional experiences. Here, it is wise to avoid exaggeration or polarisation. The authors of the HFE strategy paper neither maintain nor suggest that the HFE community should either disregard trust or promote distrust. Sadly, like so many regulators and modern custodians of professions, they simply fail to consider the critical importance of trust for the survival and growth of the community whose concerns they address.

Social intelligence in HFE practice

The point can be made quite simply: firstly, as there is no natural law entitling the HFE community to a coherent future, the task of building trust constitutes a core competence of HFE practitioners and should become a cornerstone of any strategy for developing their professional identity; secondly, this entails the task of actively cultivating social intelligence.

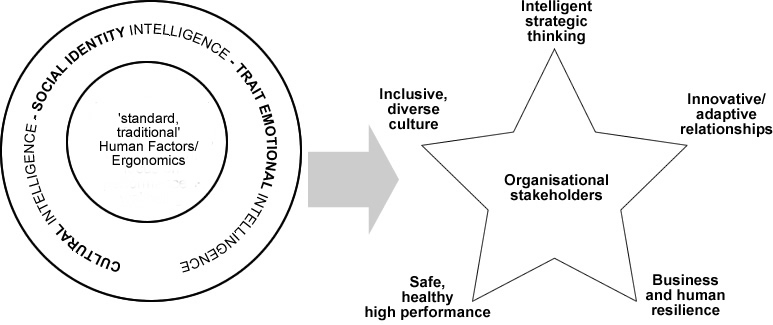

Underlying the strategy paper is an assumption that members of the HFE community should attempt to apply scientific reasoning to problems they address. This assumption applies to the principle of building trust through exercise of social intelligence in the practice of HFE itself and I will sketch how relevant research has now reached the point where three areas of social intelligence can be applied in this work: ‘cultural intelligence’, ‘social identity intelligence’ and ‘trait emotional intelligence’. Figure 1 sketches how I envisage this might contribute to needs of organisational stakeholders, transforming how HFE can serve needs of stakeholders in partnership.

Fig 1. Components of social intelligence can enrich HFE practice and foster trust

Using data on organisational culture

It is not unusual to hear HFE practitioners, like members of other aspirational professions, refer to ‘the culture of the organisation’ as a constraint on ergonomic design. Probing further, in my experience, they tend to make these comments like window-shoppers with no intention of talking about possible changes in the culture, based on verifiable data.

And yet every time a HFE practitioner enters an organisation, they are presented with data about its culture. The New Zealand organisational psychologist, Anne Marie Garden, used the expression ‘Reading the Mind of the Organisation’ (Gower, 2000) to refer to structured methods of accurately gathering, organising and interpreting data on cultures of organisation, and constructively offering it to members of an organisation to enable them to improve the quality of their decision-making and communication, reduce errors and moderate their impact. While Garden used models of personality to illustrate what she meant, research enables HFE practioners untrained in personality research to use data to represent an organisational culture in the manner encouraged by the pacemaker on research in this area, organisational psychologist Edgar Schein, who honed his own skills as an alert observer as a child refugee obliged to move home across three countries by the age of 10. Bearing in mind Schein’s explanation of how the cultural footprint of an organisation can be pieced together from evidence in the form of artefacts and stories that express values and assumptions, when a group of managers ask me about their culture in relation to ergonomics, I’m inclined to draw their attention to sets of artefacts prominent in their hallways: their – often incredibly glorious – mission statements, business trophies as well as minutes of meetings of the safety committee. The message about the culture arises from how well any managers can readily find themes common to all three sets of artefacts.

But HFE practitioners don’t need personal histories as child refugee experiences in order to develop useful skills of observation of organisational culture: those interested in well-validated techniques for gathering and using data on organisational cultures are now able to rely on such tools. Richard Butler, a clinical psychologist from the north of England, used funding from the UK Sports Council, to apply repertory grids to negotiate data to profile skills for coaching athletes (Richard was a coach to the England boxing team at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics) and published accounts of validation of the profiling tools are available. And the technique of concept mapping, developed by Cornell social science researcher, Bill Trochim, and his wife Mary Kane, is also useful for group exploration of organisational culture in ergonomic interventions; again, technical information on its validity is readily available.

Characterising social identity in applications of HFE

Like any other consultants, HFE practitioners face the task of negotiating relationships between their own social identity and the social identities of client organisations they work in.

I have already remarked about the multiple identities arising from the hybrid character of the work of many HFE professionals. What social identity research offers them is a systematic framework for understanding patterns in behaviour of groups within client systems. More often than not, trends of social mobility and of conflict, of creativity and of stagnation, can be illuminated with the aid of well-formulated questions to individuals about the beliefs that inform their views of themselves and people in other groups in their own organisation, in their customer groups, members of the public and amongst competitors and suppliers.

A simple illustration of application of social identity research emerged during an intervention in a small distribution firm, selling medical products to dentists’ and doctors’ surgeries, owned by a father-son partnership. One of the two office staff found she had very painful symptoms of repetitive strain injury, the first time something of this nature occurred in the twelve-year history of the business; she absented herself, protesting that she would ‘report’ the firm unless they resolved the problem with assurance that it would not recur. Entering the company, I quickly recognised the scale of breaches of employment law as well as the safety issue and I decided the critical factor was to find a way of establishing a conversation between the owners and the employee, one of the most directly hostile I have ever met, at first. In this instance, the relevant sources of social identity that guided how I conducted my interventions were twofold. The explicitly business source of the social identity between the owners and employee was to do with service to customers, around which both the owners and the employee were prepared to adapt roles and behaviour; the implicit source, that had the synergy to make a fruitful negotiation possible was about shared religious beliefs about fairness and personal responsibility (as the owners had initially recruited the injured employee through their religious network). The deal – consisting of a new telephone installation, transfer of the injured employee to a new role, after treatment and rehabilitation paid for by the employer, and my (modest!) fee – cost less than a third of management time or of expenses than litigation and even less than inspections by officers of the state.

Social identity research in organisations has grown steadily since it was kindled by the Anglo-Polish social psychologist Henri Tajfel nearly fifty years ago. Examples of validated scales for measuring aspects of social identity are available in the research literature including ‘Psychology in Organisations’ by Alex Haslam (Sage, 2004) who indicates how the social identity approach amplifies the human relations paradigm associated with the 1920s – 1940s Hawthorne experiments, rejecting ‘the rabble hypothesis’ in favour of principles of collaboration within working groups.

Exercising trait emotional intelligence

Although Aristotle refers to moderation of emotions in his Nichomachean Ethics some 2,300 years ago, it is only twenty years since ‘emotional intelligence’ became a focus of scientific enquiry. The area of research has grown steadily with the publication of hundreds of articles in peer-reviewed journals. A significant threshold in this research arose when the distinction between ‘emotional intelligence’ as a set of mental capabilities, anchored in problem solving, and ‘trait emotional intelligence’ which is represented as a combination of a total of fifteen factors, both personality traits and interpersonal skills.

To the extent that HFE consulting entails interpersonal interaction, and that this is as vital as Maister and his colleagues emphasise, exercise of trait emotional intelligence can contribute to the creation of value in HFE interventions. In one sense, this may appear to be just ‘common sense’ yet how common is excellence on the part of consultants (and clients) in many organisations?

This component is qualitatively different from the other two components of social intelligence in two ways. One is that the use of the language and concepts of trait emotional intelligence can function as a valuable pick-me-up when a HFE practitioner him/herself is under strain for it can be used to objectively pinpoint sources of stress, the first step in controlling them. The other is perhaps more challenging, in so far as research indicates how a group of HFE practitioners are more likely to display a trait such as empathy to a client ‘outgroup’ when their own management display empathy to the ‘ingroup’ of HFE practitioners themselves.

The value of ‘trait emotional intelligence’ revealed by research threw light on a facet of my own practice in a way that I figured out from experience: over time, I noticed how attention to emotions, especially of senior managers, made the critical difference on occasions during phases of intricate change in an organisation when behaviour of managers was the focus of concern or indeed conflict: the sense of structure and orderliness associated with the ‘TEI’ feedback was often the vital bridge to retaining essentials of trust and harmony.

Details of research about trait emotional intelligence are available on the website of its inventors in the Psychometric Laboratory at University College, London.

Are boundaries of HFE sufficiently permeable?

Rather than aspiring to take ‘the language of stakeholders as the main actor’, the HFE community is more likely to win acceptance through synergy possible through social intelligence. As good leadership and parenthood normally start with conversations, fruitful use of social intelligence does too. While ‘mentoring’ has become part of standard practice in the HFE community, as it is commonly understood it may well be too associated with hierarchical uses of power and authority to be used as the main vehicle for advancing the practice of social intelligence well. Various forms of coaching – professional, managerial and ‘peer-to-peer’ – mean that, once there is a shared understanding of the essentials, it can become a valuable form of facilitation enriching HFE practice.

It remains to be seen to what extent the boundaries of HFE are sufficiently permeable for practitioners to align with stakeholders fostering trust in partnership, rather than to dwell on aspirations about HFE as the ‘main actor’, like Alice in Wonderland.

An accomplished writer and speaker about business psychology and ergonomics at work, Kieran Duignan has degrees in economics, psychology and ergonomics and diplomas in counselling, career guidance and executive coaching. He has been a staff tutor at the University of East London and a visiting tutor at University College, London and the University of Surrey. He has served as an expert witness about claims in the areas of personal injury, unfair dismissal and unlawful discrimination.

This article originally appeared in The Ergonomics Report™ on 2012-10-04.